CERF Blog

Written October 21, 2022

The fundamental question for the U.S. macroeconomic forecast is if the pandemic recovery can continue or if the economy is heading into a recession. This outcome will be determined largely by Federal Reserve actions during the quarters ahead. Given how long the Fed waited to fight the current bought of inflation, it is not likely they can return inflation to its target rate without monetary policy changes which would also induce a recession.

It is an open question if the Fed has the fortitude to follow-through fighting inflation. The forecast then, is either for recession, or anemic growth accompanied by continued inflation.

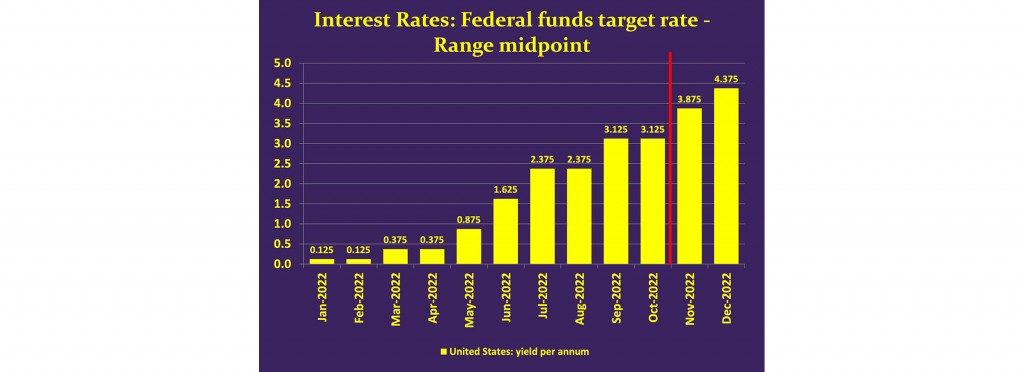

CERF’s baseline forecast embodies the assumption that the Fed will cease substantive hikes by December 31st of 2022 and that the economy will not be pushed into recession. We do have one 25 basis point hike in early 2023, but no other hikes. This is a low confidence forecast, since it necessarily involves predicting the behavior of a body of political actors at the Fed.

This forecast for the Fed’s policy rate has implications for inflation. Inflation, with substantial momentum at the current time of writing, will not be much reined in by this forecast of Fed policy.

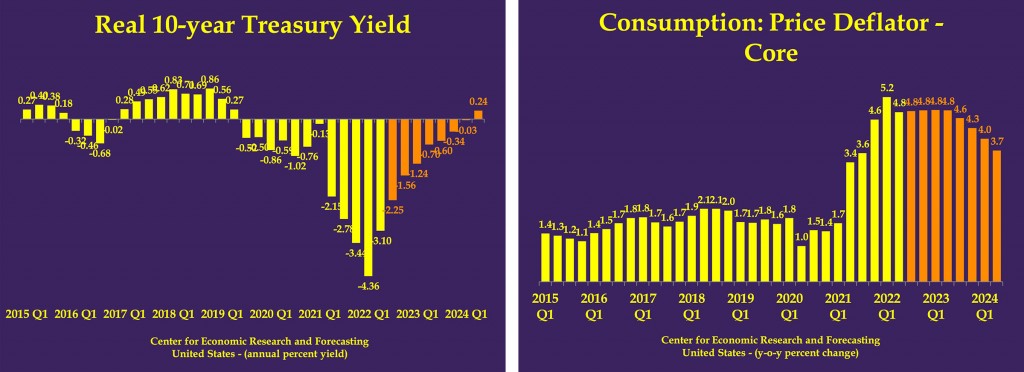

How strong is the Fed’s policy stance on inflation? The real ten-year Treasury yield was -3.1 percent using September yields with the core PCE deflator. As conventional wisdom has always argued, a negative interest rate of that magnitude indicates policy that is massively stimulative.

The presumed level of short term interest rates under this forecast scenario is that they reach 4.625 percent (based on the midpoint of the Fed’s target range) by mid-2023. By the Fed’s own analysis the rate needs to be above 6 percent in order to adequately combat inflation.

Inflation will subside, but it will not subside quickly, and the real 10-year Treasury yield will remain in negative territory for all of 2023, indicating that instead of being restrictive, the Fed’s policy will remain stimulative, for about a year.

We forecast that the Core PCE deflator will still be 4.8 percent at the end of 2022, and that it will still be 4.3 percent at the end of 2023. This is higher than the consensus forecast of 3.2 percent, but our forecast is lower than inflation expectations, such as the University of Michigan’s survey value of 4.8 percent.

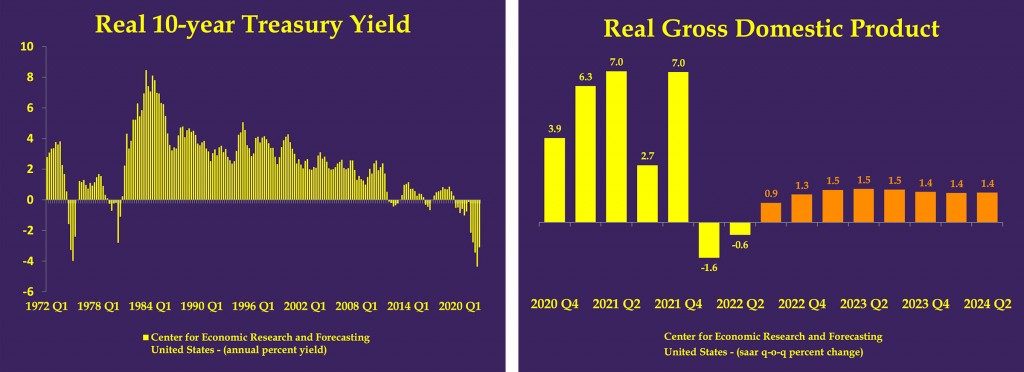

This forecast is one where rates are not really that high. The chart below shows the third quarter real 10-year Treasury is still quite negative, and it shows real rates during the Volcker policy era in the early 1980s that did succeed in fighting inflation, and also pushed the economy into recession.

Because rates are not really that high, inflation will remain persistent, and, growth will be weak but positive. We do not forecast a recession in this scenario, in part because rates are not actually that high. They will not get high enough to halt inflation, and they will not be high enough to cause a recession.

CERF has argued that monetary and fiscal policy has been much too stimulative. While it is possible to justify stimulating the economy in the time of crises, policies have been a ratchet, ramping up support through payments and credit in times of crises and not subsiding thereafter. This occurred after the 2007-08 financial crises and again during the Pandemic in 2020.

Overly-stimulative policies help us understand the macroeconomic environment we are in today. Some forecasters are saying that the Fed’s impotence against inflation, with 300 basis points of hikes in seven months having failed to slow inflation momentum, has surprised almost everyone. This does not surprise CERF. The economy is overstimulated. According to CoBank estimates the U.S. household sector still has $2 Trillion in excess savings. And, we point to the most recent University of Michigan survey data, which as of October showed consumer’s expect inflation will still be 4.8 percent a year from now.

There are risks to this forecast. One alternate scenario is that the Fed does continue raising rates aggressively during 2023, sending the short term policy target well-over 6 percent. In this scenario, the real 10-year Treasury yield would surge into positive territory more rapidly, inflation would subside more quickly during 2023, and the economy would experience a recession.

Why is our baseline case that the Fed does not get in front of inflation? They have shown before that they are sensitive to markets, especially, the stock market. In October of 2018, they announced a balance sheet normalization policy that sent the S&P 500 into a 24 percent decline in just 3 months. On January 4, 2019, Fed chair Jerome Powell signaled a reversal of policy normalization, and in March of that year, stated that a multi-trillion dollar balance sheet might go on indefinitely. This of course, gave rise to the notion of QE-infinity, the idea that the Fed would never normalize policy.

The effect of significantly higher rates will have an important follow-on effect of raising the debt service costs for the U.S. This is more of an issue now, where the debt to GDP ratio is 120 percent, a historically high level for the U.S. This will be another source of pressure against further Fed rate hikes to levels above 5 percent.

CERF’s economic forecast for the next eight quarters is for growth substantially below potential. Many forecasters, including the Fed, point to demographic factors and make post-industrialized economy arguments to rationalize below potential growth. CERF disagrees. Most of the sub-par growth is driven by poor policies, policies that throw a blanket on what would be a much more healthy and robust economy.

Monetary and fiscal policies should follow policy rules, or a logic that is guided by economic theory and analysis. Policies since 2008, especially monetary policy, have been ad hoc. They depress economic activity through the specific disincentivizing impacts they impart on investing for the future, but in addition, they depress the economy through policy uncertainty. This uncertainty doesn’t just add difficulty to forecasting, but it also reduces the ability of households, establishments, and governments to make decisions for their, and the our nation’s, future.